1. Introduction

Como’s historic promotion to the Serie A marks the end of a long period of suffering for the club. Since their last appearance in Italy’s first division, back in 2002/03, the Biancoblù have gone into bankruptcy twice while struggling in the country’s lower leagues. In 2019, following the club’s most recent financial difficulties, Como were acquired by the Djarum Group, which curiously includes Thierry Henry and Cesc Fàbregas as minority shareholders. After back-to-back 13th-place finishes in Serie B, the Lombardy club secured automatic promotion with a second-place finish this season.

Cesc Fàbregas was appointed as the interim manager in November 2023, a few months into the season. According to ESPN, Fàbregas was given a temporary permit by the FIGC as the Spanish manager did not have the required coaching qualifications. After its expiration, the club hired former Wales assistant manager Osian Roberts, with Fàbregas remaining a part of the coaching staff. Despite taking charge of the side for the rest of the season, Roberts was hired as the club’s Head of Development, a role he will exclusively assume heading into next season. With a unique coaching situation, the Biancoblù found consistent success in the second half of the season.

Tactically, Como were incredibly intriguing, particularly in possession. With their own twist, Fàbregas and Roberts’ attacking approach contained many ideas resembling the growing style of relational football. In a detailed breakdown, this tactical analysis takes an in-depth look into the attacking tactics behind Como’s success in 2023/24.

2. Overview

Before diving into the tactics, this section provides a statistical overview of their work in possession. With 21 matches in charge, Roberts won 12, drew six, and lost three. In this period, Como outperformed their rivals with 1.52 xG against 1.02 xGA per 90. Similarly, they scored 1.81 goals while conceding 1.10 goals per 90. This superiority continued with 13.24 shots and 8.86 shots against per 90.

Their style can begin to be illustrated through a few attacking metrics. Como’s 52.93% average possession under the Welshman indicates a slight but hardly significant superiority. The same trend can be observed for passes per 90.

More indicatively, they averaged 3.99 passes per possession compared to 3.69 from their opponents. This metric is quite useful in illustrating how likely a team is to retain and control the ball. For reference, Catanzaro led the Serie B with 57.23% average possession. They averaged 5.01 passes per possession compared to 3.78 from their opponents. Similarly, 9.3% of Catanzaro’s passes were long passes. Under Roberts, 11.72% of their passes were long passes. Como’s attacks were not characterised by looking to retain and control possession, and this brings us to their tempo.

Pep Guardiola’s 15-pass rule refers to the broad idea of keeping the ball to establish control and get organised before attacking. Without significant retention or control, Como played at a very natural tempo. At a collective level, there wasn’t significant pause or desire to slow the game and dictate the tempo. Nonetheless, they executed their tactical ideas extremely well, finding organisation through principles and structural behaviours.

3. Players and Shape

Como set up in a 4-2-2-2 shape with a consistent core of players. Adrian Šemper was the goalkeeper behind Alessio Iovine, Edoardo Goldaniga, Federico Barba, and Marco Sala. Cas Odenthal was an option for Barba, and Nicholas Ioannou could replace Sala at left-back. Although Daniele Baselli was an alternative, Alessandro Bellemo and Matthias Braunöder consistently formed the base of the midfield. The Brazilians Lucas da Cunha and Gabriel Strefezza played as inside forwards behind Patrick Cutrone and Alessandro Gabrielloni. Simone Verdi was an option as an advanced midfielder while Nicholas Gioacchini offered a different dynamic up top. Altogether, this XI, along with a few alternatives, provided a consistent platform for Fàbregas and Roberts’ tactics.

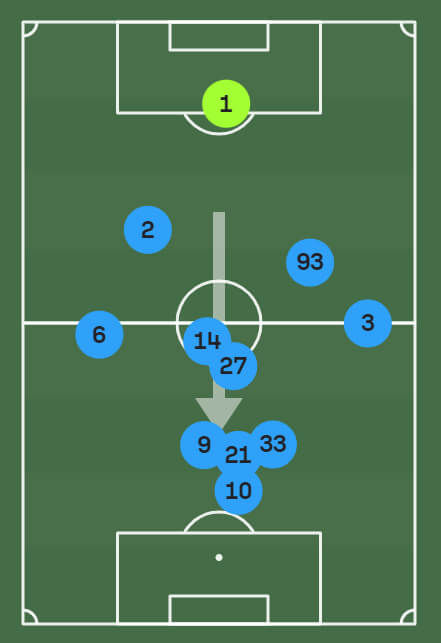

Going to the pitch, Como’s players (in white) can be seen organised in their 4-2-2-2. Ahead of the back four, the double pivot engages behind the first line of pressure with the two inside forwards positioned within the opposition’s defensive block and the two strikers near each other on the last line.

There were a few dynamics emerging from this shape. The first is the minimum width created by the 4-2-2-2. Rather than a traditional 4-4-2, Roberts’ shape did not have wide attacking players, and this significantly influenced the mechanisms of their attack.

SofaScore’s average positions map against Cosenza further illustrates these dynamics. The lack of width in advanced areas quickly stands out, but the proximity between the advanced players is significant, even between the two deeper midfielders.

This can be further understood through a perspective introduced by Antonio Gagliardi in his recent article. Como’s structure has five (six including the goalkeeper) perimeter players and five relational players. Although superficial, this categorisation is a useful tool to visualise the general dynamics of the structure.

The back four are stable in their positioning, providing a more fixed reference to the structure. The deeper midfielders are always moving together, and the inside forwards are quite free in their movement. Up top, Cutrone performs a similar function to Zirkzee at Bologna, maintaining depth but also capable of dropping.

This brief first video provides a look into the shape in practice and identifies a few of the dynamics explored, namely the minimum width, proximity between players, and the perimeter vs. relational players, with Verdi (#90) even dropping in to get on the ball.

This second example shifts the focus strictly to Gabriel Strefezza (#21), perhaps the most relational player in the team. In the video below, he can be seen roaming from his initial position. It is especially curious how the other inside forward, da Cunha (#33), roams with him as well.

4. Playing Near the Ball

Como take the minimum width from the shape a step further. The deeper midfielders normally move together and stay close to each other, usually with the ball as the main reference. The inside forwards look to do the same. Up top, the two strikers are more stable in terms of depth but still tend to remain close to one another. Cutrone is capable of dropping at times, though.

The proximity and ball-oriented movement of these players will often result in their shape collapsing around the ball, creating structures commonly found in other relational sides. The example below clearly illustrates this unit of four in the midfield staying close to each other and looking to play near the ball.

The video below provides two more instances of Como creating these structures. Again, the four midfielders are the ones offering more movement while the back four perform the perimeter function. In both clips, it is also clear how Cutrone is more inclined to interact with play below him while Gabrielloni tends to be more fixed.

4.1. Functionality

In the more relational sides, once in these structures, there tends to be significant roaming and interchange of spaces. That is not the case for Como, who function in a sort of “in and out” way. Normally maintaining their positions in relation to one another, simply collapsing the shape, they will look to combine their way through or around the opposition. Rather than creating opportunities through disorganisation and chaos, they move the ball through the structure and react accordingly. The exceptions are, of course, when Strefezza or da Cunha roam more significantly.

This structure can lead to overloads around the ball, facilitating the progression through the opposition by simply having too many options to close down. Overloads are a common consequence of these structures, but they only tend to be successful when exploited quickly. Normally, defences won’t take long to congest the area.

Como will often use these structures as a platform for quick combinations forward. With players closer to each other, there are more possibilities for passing combinations, and at a high tempo, these can be extremely dangerous.

It may become ugly, but the counter-pressing offered by these clusters can be very effective. With such a high number of players close to the ball, if possession is lost, it is easier to compress the opposition, minimising space and closing options. In the instance below, they lose the ball twice but instantly recover it to keep moving forward.

While they can be found in all thirds, runs behind become more significant in the final third. Players will attack the depth with runs, creating passing options, lowering the opposition, and creating space for others. With these, interchanges become more frequent, particularly through counter-movements (attack vs. support, vacate & appear). These all serve to disorganise the opposition and create opportunities to progress forward, and again, these become more relevant in the final third, albeit they can still appear elsewhere.

It is worth noting that individuals like Cutrone, da Cunha, and Strefezza are extremely technical and resourceful players. These structures promote them playing together, and in some instances, their individual brilliance and creativity alone are enough to unlock opportunities.

4.2. Escadinhas

Intentional or not, escadinhas (ladders) are a relevant theme in Como’s possession. Again found in relational sides, these are instances where usually three players will form a vertical or diagonal line. Como’s shape (4-2-2-2) and the dynamics (proximity near the ball) tend to naturally and frequently create these instances throughout the pitch, and they can be a useful resource to progress forward.

As far as who creates them, the options are endless. In the examples we will observe, they emerge as FB-ST-ST, CDM-CAM-ST, CB-ST-ST, FB-CAM-ST, or CAM-ST-ST. However, they appear so naturally that they can involve any combination of players. They are used either as a corta-luz (dummy) and/or turning and playing. In the instance below, these vertical and diagonal lines can be seen appearing throughout their attack.

In the next example, the escadinha is created through the full-back (with the ball), the first striker (dummy), and the second striker (receiving). While the execution fails, the idea is there. It is also a useful example to display once again how their proximity helps them react with success after losing the ball.

While unsuccessful, these two other examples show how they tend to create and use this resource.

5. Aggressiveness

Perhaps influencing their possession metrics, the Biancoblù can be very aggressive in their attacks. As mentioned in the beginning, Roberts’ men do not necessarily favour retention or control, and they are happy to quickly play forward. Without a pause, they can find organisation through ideas and structures. This section expands on this aggressiveness to outline some of these ideas and the role the structure plays in them.

5.1. Vertical Sequences

Como’s attack can progress forward through fast and vertical passing combinations, and this is largely afforded by their shape and dynamics. As previously observed, the proximity can offer more possibilities for combinations, and the different heights created by their shape potentializes the verticality of these sequences. Third-man runs, one-twos, and escadinhas are all relevant here.

This verticality is more relevant in the first two phases of possessions, albeit there are various examples in the final third as well. Through a few examples, we can visualise these sequences more clearly. The one below includes two instances; the first helps slightly lower the opposition and keep circulating the ball, and the second helps them break into the final third.

In another example, the potential for vertical attacks brought by the shape is perfectly explored in the first phase of possession and helps them break into the final third to create a chance.

Now in the middle third, this sequence is performed by the left-back, the inside forward (who drifts wide), and the first striker. The left-back makes an inverted run to create the third man before finding the second striker directly into the final third. A high-tempo vertical sequence takes them from the middle to the final third, and they do extremely well to arrive in the box with five players.

Finally, in the creation of a goal, the centre-back finds the inside forward who immediately turns and finds the striker into the final third, almost through an escadinha of sorts. The striker finds his partner in the box to finish a beautifully created goal.

5.2. Runs Forward

Their movement off the ball also contributes to the aggressiveness of their attacks, particularly by constantly looking to make runs forward. These are extremely simple, but they are very relevant throughout Como’s attacks.

The minimum width from their shape potentializes runs from the inside channels into the wide areas. These will often be made by the inside forward when the fullback has the ball, as seen in the three instances below.

While that is the most common dynamic, it is not the only way. This idea serves as a general principle in their attacks, influencing players’ decisions and creating an aggressive attacking environment.

6. Direct Play

6.1. To the Strikers

Como were also successful through their direct attacks, taking their verticality a step further. Whether from goal kicks, in the build-up, or into the final third, they are comfortable playing a long ball into their two strikers. The shape is great at supporting these long balls as with two midfield units crashing in front of the strikers, they are more capable of winning second balls and combining forward.

Cutrone and Gabrielloni have performed excellently on the receiving end of these, working extremely well off each other. Staying close to one another, they are always “ready” to be the long option. While one goes up for the aerial duel, the other looks to win the second ball. This second striker will either go behind for the flick on or in front for the lay-off. This has proved to be a useful resource for Como to get into the final third or even create chances.

6.2. Runs and Second Balls

With two lines of midfield crashing in front of strikers, the Biancoblù are usually in a good position to win the second ball. In the first instance below, as Gabrielloni goes up for the challenge, there are three players approaching him ready to secure the second ball. The second instance is much more scrappy, but it highlights their ability to support these long balls with numbers and find a way to come out with the ball.

With the numbers coming from behind, they are able to immediately support the second ball with runs and combinations. In the three instances below, they quickly get options around the ball and transform the long ball into sustained attacks in the final third.

6.3. Outside Pockets

As explored with the runs forward, their shape naturally creates outside pockets for the advanced players to make runs into. This applies to their direct play as well, with the strikers and inside forwards often making runs into these pockets. These long passes are easily supported by the fullback, defensive midfielder, and inside forward if the striker is the target.

7. Conclusion

Como secured a historic promotion back to the Serie A after 21 years of struggles. Their season was marked by an unusual coaching situation, but the Biancoblù found consistent success in the second half of the season. Tactically, Fàbregas and Roberts introduced an aggressive approach with interesting dynamics. It will be curious to see how this project is continued in Italy’s first division next season.

Comments